The whole surface of the earth seemed changed—melting and flowing under my eyes. The little hands upon the dials that registered my speed raced round faster and faster. Presently I noted that the sun belt swayed up and down, from solstice to solstice, in a minute or less, and that consequently my pace was over a year a minute; and minute by minute the white snow flashed across the world, and vanished, and was followed by the bright, brief green of spring. - H.G. Wells, The Time Machine, 1895

When my daughter was born, I watched the sky during rare stretches of the night. I registered the changing quality of the sky, and became conscious of the rotation of the Earth and the movements of the atmosphere. Through this focused observation, rarely practiced in our synthetic environments, I found a new channel of perspective.

Archaeological evidence suggests that human ancestors used lunar cycles for subsistence purposes as early as the Middle Paleolithic (c. 100ka).1 Researchers argue that coastal populations, surviving on shellfish, would have required some method of recording and interpreting patterns in the lunar cycle. Aristotle sketched an outline for this process as empeiria, a mode of knowledge that mediates between direct sensing of nature and the universal truths. Yet with Pliny we see the more precise use of the latin observatio as formulaic collection of a distinct environmental sensation, made distinct from the knowledge gained in singular experiences. This interplay between observation and experience is perhaps fundamental to human perception.

Techniques for celestial observation were refined in the Middle Ages by monastic cultures seeking precise schedules for prayer. Methodical observation became correlated with the search for spiritual insight, and was itself co-opted into ritual behavior. In some cases, ritual architecture even became a device for sample measurement. The monastic process fed into scientific methods of empirical observation in the early modern era, and spiritual inquiry still underlies contemporary astronomy.2 Since the 1970s, James Turrell’s “naked eye observatories” use architecture to guide focused, communal observation of changes in the appearance of the sky, a context that implies spiritual seeking.

Scientific collaboration has led to the sharing and aggregation of observations. As early as the seventeenth century meteorological observing networks began to create global data sets, leading to a mode of collective perception that has been called the “communality of data”.3 Christian Marclay’s The Clock (2010) cultivates this phenomenon, dissolving the signature gazes of cinema into a fixed, collectively experienced timebase.

Meanwhile, sensor technology has enabled automatic observation, which alienates the human observer. Samples from remote sensing devices allow unprecedented access, such as the Anarchist prints by Laura Poitras (2016), yet the images are trapped in a technical domain, sharply dislocated from both subject and viewer. (Her reframing of them is an attempt to give them context).

Observation satellites combine these two modern effects of communality and alienation in a single act of sampling. A Landsat device captures a thin band of land color as it orbits the planet, and these threads are stitched together to form a wider view, a quilt depicting many strands of spacetime. These photomontages represent no tangible reality that a person might ever experience. Like an image of deep space warped by its dependence on lightspeed, the means of sensing distorts the representation away from human perspective. Tied as we are to a specific framework of time and space, this image implies a view of the world that is outside direct human experience.

However, the human gaze is overly diluted in these images, they feel like the mechanical results of formulas for spatial capture. The culture of science values the objectivity that comes from the averaging and arranging of sensation.

Yet it is the physical presence of the time traveller in a warped view of spacetime that brings insight to Wells’ reader. His interaction with the environment gives meaning to this other experience of Earth. The artist often takes this role. In the pursuit of knowledge, Paul Cézanne argued that “in order to make progress, there is only nature, and the eye is trained through contact with her...we must render the image of what we see, forgetting everything that existed before us.”4

This need to “forget” motivates the adoption (and adaptation) of image capture technique from science, as they are necessarily agnostic to the rigid culture around a medium. It also motivates a return to simple questions about our surroundings. Wells implements a machine as a vehicle for expanding his description of time.

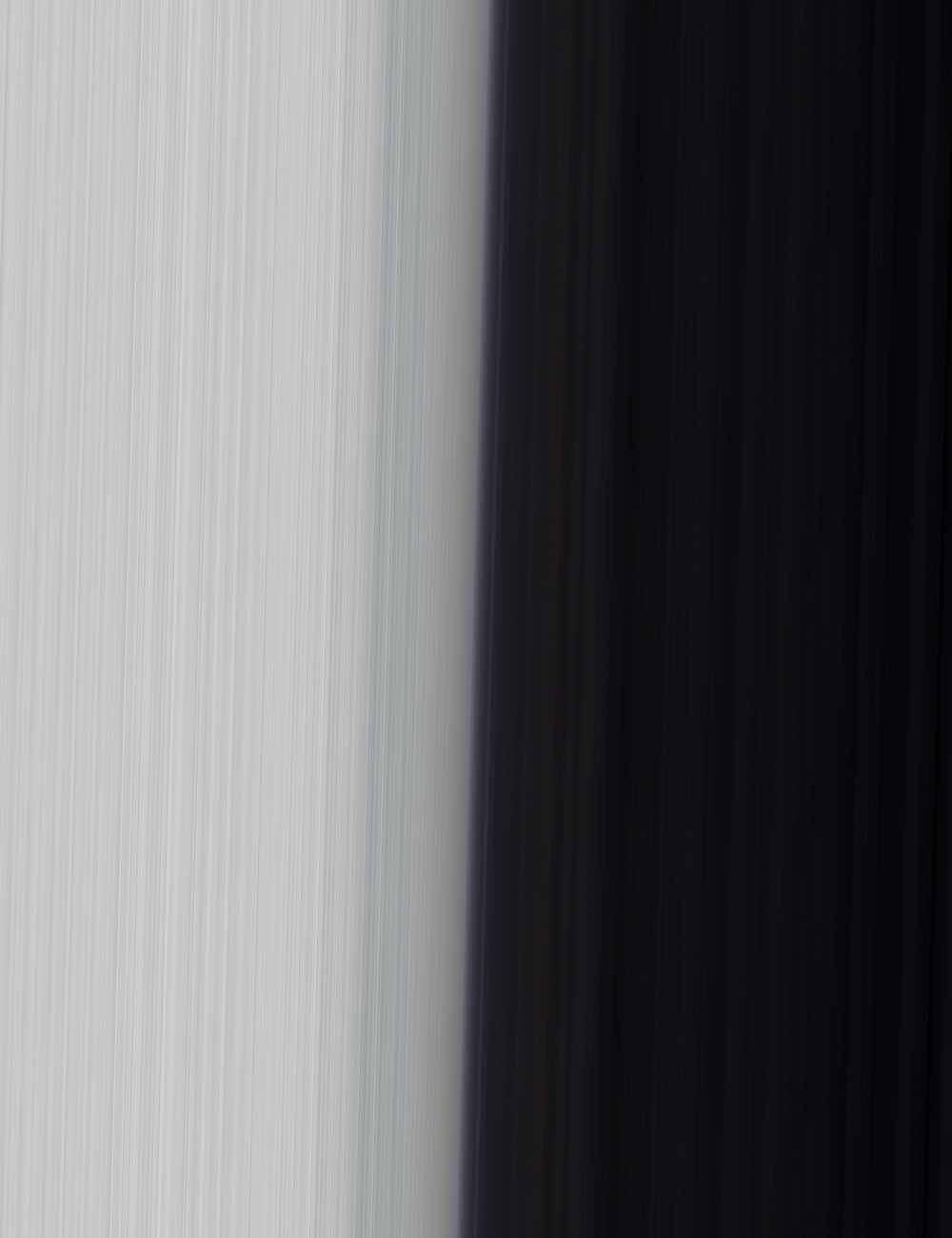

I began experimenting with recordings of the sky in Berlin, and built a camera to record color values over long stretches of the day. I record the color of a single pixel of the sky at short intervals, and over long durations. I then re-write the color samples to sequential bands in a single image, evocative of the color fields of Gene Davis or Kenneth Noland during the 1940s and 1950s, yet premised on empirical data. The images are pigment printed and built into a perceptual window, using layers of glass and internal framing to create an illusory device that evokes orbital perspective. Through this altered mode of viewing, the unique forms of atmospheric information become layered into a single landscape carrying a diversity of readings: light pollution at a fixed position presented spatially, weather conditions across a hemisphere outside linear time, or a snapshot of the state of Earth’s rotation in reference to the Sun.

My intention is to create new, expansive views of my atmosphere in spacetime, using the rigorous, experimental sampling techniques of scientific research while avoiding the communality and alienation they breed. It is an attempt to hybridize the exploratory capacity of scientific technique with the presence of the artist. This reflects the integration of observation and experience in the monasteries, seeking a personal impression of the unknown through the technical expansion of direct human experience.