Shepherds gather at a tomb in a pastoral landscape. A skull on the tomb speaks its inscription, "Even in Arcadia, there am I", an intimation of the universality of death. This scene, originally depicted by Guercino (c. 1620), is premised on a narrative in Virgil's Eclogues. A remote enclave of the Peloponnese, Arcadia is framed as a utopian alternative to the urban culture of Hellenistic Greece. The introduction of this memento mori is meant to undermine the pastoral ideal. In the most analyzed rendering of the scene, by Poussin (1637-38), the shepherd touches the inscription. He seems to trace his own shadow on the tomb, a dark figure that stands in for Guercino’s skull. He crosses the boundary of Arcadian life to make contact with this reminder of his mortality, yet his gesture also evokes the prehistoric discovery of painting.1

Painting landscape, I have crossed boundaries in search of a composition and found myself on private property. Treating the land as an aesthetic subject, I am released from the constraints of land ownership. When reminded of the boundaries by a rock wall, the landscape becomes an elusive paradise where my own presence is invasive.

Village Homes, a planned community I studied in Davis, California, is an inversion of the suburban planning model which emphasizes pedestrian scale and biology over the machine infrastructure. Yet I came to realize that for the residents it is still a bounded world, a structure that opens up the pitfalls of the paradise myth. We seek utopia as a way to escape death in all its subtle manifestations, but mortality violates the premise of the Neolithic paradise that continues to drive that utopian ideal in the West.2

Berger notes that Poussin was a contemporary of Descartes, and sees in his shepherd an attempt to reconcile the alienation between self and nature that is epitomized by the Cartesian division.3

So I embrace my instinct for incursion, to deconstruct the myths that so shape the perception of land, and thereby extend the artist's access to landscape as subject, and transitively, as devices for self-study.

The information being created by Earth-observing systems is relatively agnostic to boundaries. A satellite's gaze transgresses legal boundaries while continuously capturing environmental data. The result is an open model of landscape. This open model is not new. Painters in the Hudson Valley School used information from stories of the frontier to expand their subject matter beyond the reach of their physical presence into meaningfully inaccessible landscapes. Rousseau painted from garden recreations of exotic forests. Richter used photographic evidence as his subject. But the current models have resolution that allows us to have a complex, physical encounter with a foreign landscape that parallels traditional picture making sur le motif. The motif here is sensor data. If sensor technology is an extension of the human, then we simply continue to create pictures in dialogue with our sensory system.

Thomas Ruff has explored landscape through land color and elevation data, but his seeking is limited to a set of views defined by the Mars Science team's imagery. By inheriting these found images, the process is bounded by scientific methodology. Although these frames have value for him, my interest in an open field of inquiry is directly counter.

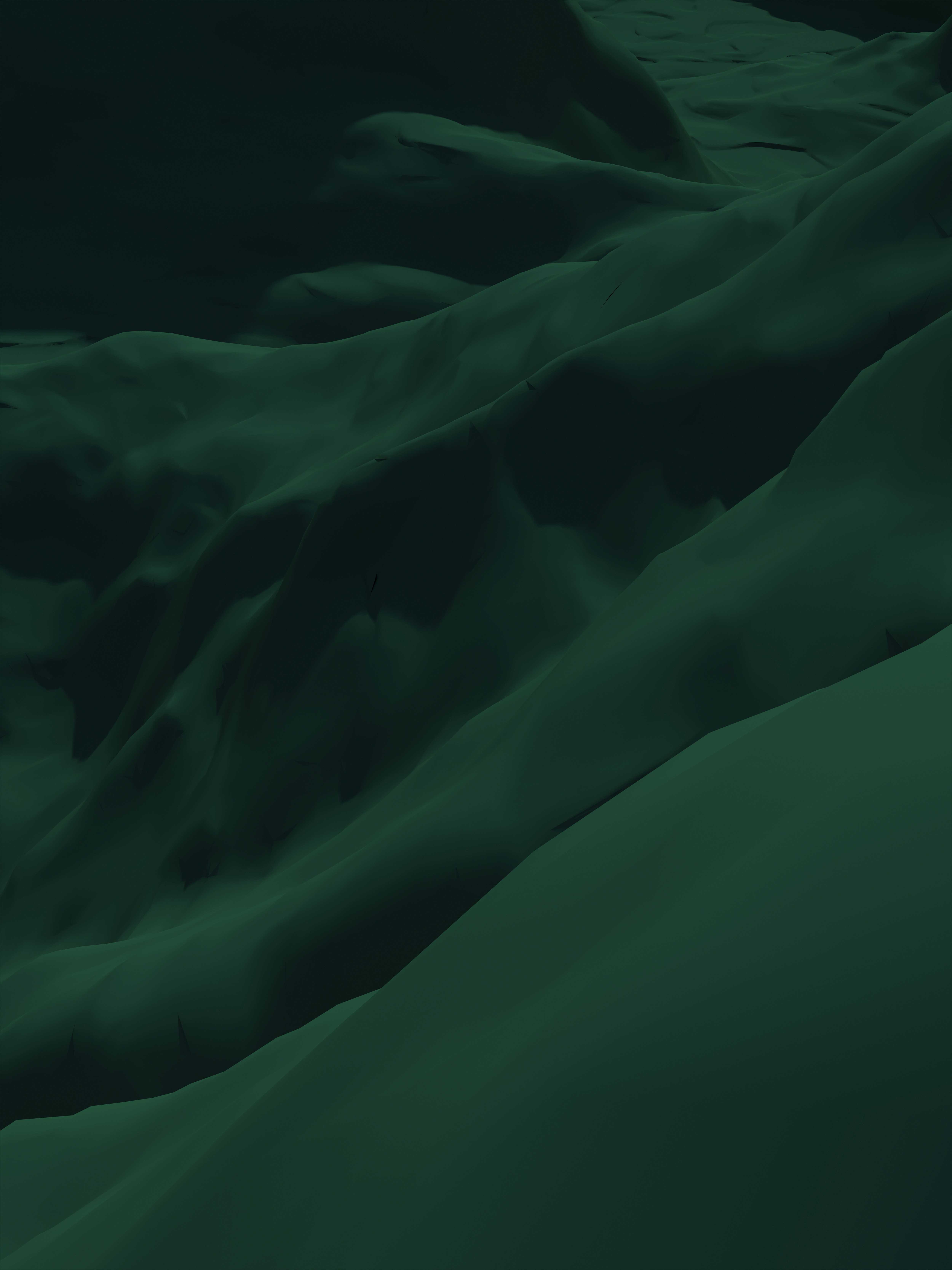

The first step is a search for private land. Karwas and I use property data from the global real estate market to identify large tracts of undeveloped land that is for sale. In particular we look for land with rich vegetation and complex terrain, evocative of a private Eden. As an initial subject, we decided on an expansive property near the Cisnes river in a remote area of southern Chile. Aster GDEM V2 elevation data of the region is used as basis for a polygon model of the terrain, and solar position data simulate the interaction of light and surface at a specific day and time. I use a virtual reality headset to explore this terrain model, trekking freely across the landscape at human scale. Despite an uncanny environment, the process is still familiar; I find a composition, frame a virtual camera, adjust lens and exposure, and use it to create a rendered image. The output is essentially a shadow drawing, devoid of specific color.

Andreas Gursky has worked from elevation and land color data to craft perfected landscapes of the oceans. Putting aside his use of subject curation, his interest in the way bathymetry data shaped color values led me to explore the interaction of terrain shading with a single hue. I sample an average hue value from the local color and use it to create a tonal foundation for the shadow image. By separating color from shade, I separate the two data sets as pictorial objects, each possessing its own resolution and manifested to reflect the way light would be expected to interact with the source phenomena in nature.

Forced into an uneasy dialogue with the shadow's presence, the viewer is put into the role of trangressor.

- Gabriel Winer